What Grand Prairie gained — and what we’ve lost — by switching to single member district representation

At-Large vs. Single-Member Districts in a Changing City

A recent conversation between Councilman Junior Ezeonu and Mayor Ron Jensen on Councilman Ezeonu’s FairPlay Politics podcast about gerrymandering got me thinking about representation — not just at the state and federal level, but on city council and our school districts. That reminded me of an old Grand Prairie Daily News article I’d come across a few months ago while researching another project. It was about single-member districts….One clipping led to another, and before long I was in a full-on historical rabbit hole.

I’m not making a case for or against single-member districts. (At this point, that debate is not going anywhere). My curiosity is whether they’ve really helped Grand Prairie achieve better representation over the last 50 years.

The 1970s: How We Got Here

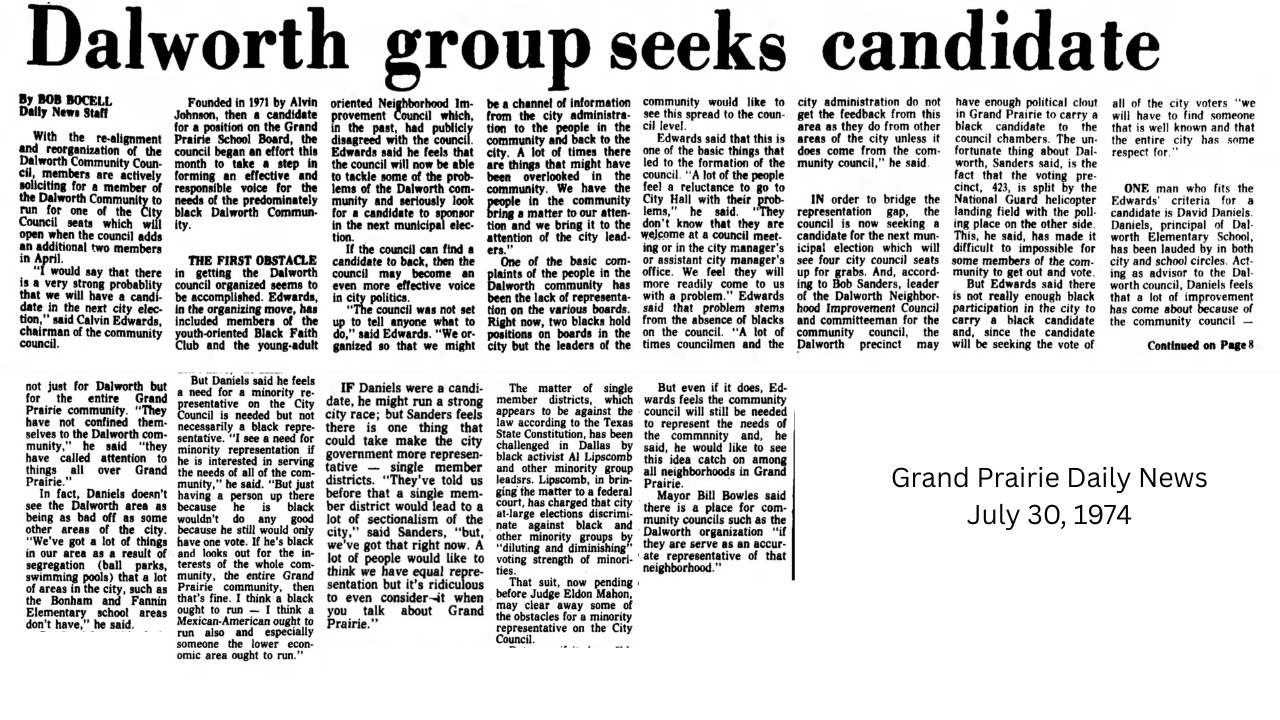

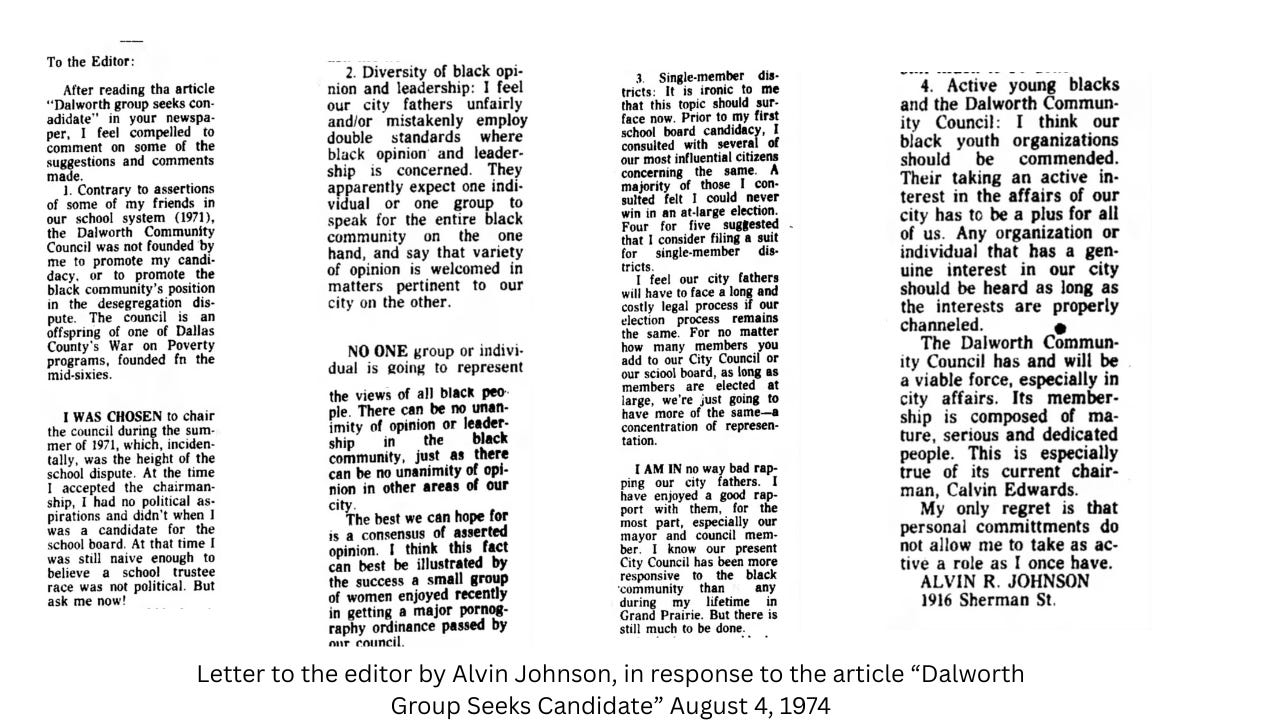

In the 1970s, Grand Prairie, like much of the nation, was coming out of segregation. Dalworth was the Black neighborhood at the time — self-contained, with its own school system, but also home to strong, educated, and persistent leaders. They never stopped pushing for a voice on city council.

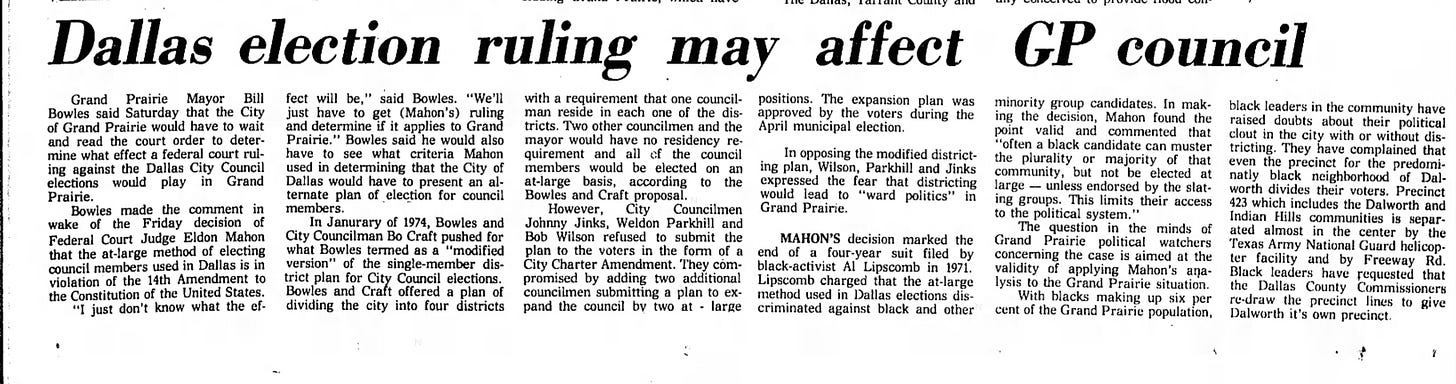

Meanwhile, lawsuits and court rulings in Dallas County were striking down at-large voting systems. Judges ruled they were unconstitutional because they favored affluent candidates and excluded poorer and minority communities. That push spread to cities like ours.

In Grand Prairie, a former councilman led the charge, eventually forcing the city through legal channels to adopt single-member districts. Not everyone agreed.

Even within Dalworth, leaders like Principal David Daniels stressed that representation wasn’t about electing someone of a certain race — it was about electing someone who would stand up for Dalworth and still make decisions in the best interest of the whole city. Alvin Johnson, another civic leader, felt differently: after being told he couldn’t win at-large, he came to see single-member districts as necessary.

At the time, Mayor Bill Bowles opposed the change, warning against “ward politics.” Others shared that view, but many also saw the writing on the wall. By the mid-1970s, the Dallas County Community College District and then local school districts began moving to single-member districts too

.Eventually, a modified single member district plan would be implemented in Grand Prairie, in which three of the council members (the mayor and two others) would remain at-large, while the rest would be from a district. This is the plan we follow today.

Why They Mattered Then

Looking back, single-member districts made sense in that moment for three reasons:

Segregation and redlining had left neighborhoods racially divided and excluded from power.

City priorities were uneven, with certain areas receiving attention and investment while others were neglected.

Candidate pipelines were limited — some neighborhoods simply had fewer people with the name recognition to run at-large campaigns.

In that environment, single-member districts opened doors that might have otherwise stayed closed.

The Reality Now

When Grand Prairie adopted single-member districts, the push was rooted in ensuring racial representation. Decades later, the city is far more diverse overall. Today, the sharper lines aren’t just racial — they’re socioeconomic.

Home prices, school district boundaries, and neighborhood amenities create as much division as demographics once did. A family in a half-million-dollar home near Mansfield ISD experiences a very different Grand Prairie than a family living in a more affordable ZIP code within GPISD. Those contrasts shape priorities and politics, and the smaller the districts, the more those divisions can harden.

So while the original system was designed to open doors that had been closed, it now sometimes functions to reinforce boundaries — not always racial, but increasingly economic.

Economic Development

Grand Prairie has always prided itself on economic development, and the city is still growing fast — annexing new land and expanding its footprint. But resources tend to follow the projects of the moment. Right now, that means heavy investment around Epic Central, downtown revitalization, and development in the southernmost parts of the city.

That’s another challenge with single-member districts. When attention and money are concentrated in certain areas, representatives from other districts often struggle to bring resources back home. Instead of thinking about how to balance growth citywide, the council can tilt toward the districts where the biggest projects are underway.

The Candidate Pool Problem

One of the biggest challenges with Grand Prairie’s single-member districts is not how council members vote, but who actually runs. By carving the city into small slices, each election depends on a very limited pool of people who just happen to live inside the lines.

That sounds fair in theory — every neighborhood gets its own voice. But in practice, some districts have a strong bench of engaged residents ready to serve, while others barely see anyone step forward. More than once, voters have faced the choice between a single unopposed candidate or someone running simply because no one else would, which doesn’t lead to better representation.

Who Can Actually Run?

The reality of local politics is that being a council member or trustee takes enormous time and resources. Most people simply can’t afford to serve. In practice, candidates are often those who have the financial flexibility: they own a business, have a spouse with enough income to carry the household, or work in fields like real estate or consulting that allow flexible schedules.

They are rarely hourly employees, people with rigid 40-hour jobs, or parents of young children who can’t juggle both family life and the nonstop calendar of events that public service demands in Grand Prairie. That doesn’t mean they aren’t qualified — but it does mean the candidate pool is already filtered by wealth, time, and connections before the first vote is ever cast.

Easier to Exploit

Another drawback of single-member districts is how easily they can be exploited. In an at-large race, a candidate has to appeal to the city as a whole — meaning broad coalitions matter more than narrow loyalties. But in a small district, the math changes.

It takes far fewer votes to win, which makes these races ripe for partisan maneuvering. We’ve seen it in Grand Prairie: the most heated, partisan fights over the past year weren’t for citywide seats — they were in single-member council and school board races.

And it didn’t take long in the 70’s for the parties to figure this out. As soon as the system was in place, both major parties began eyeing those smaller races as low-cost, high-impact opportunities. What was once a system meant to increase representation can just as easily become a political chessboard.

So, Where Does That Leave Us?

I don’t think single-member districts today guarantee better representation any more than at-large systems do. Both can fail when leaders forget who they’re really serving.

At-large elections can shut out minority and low-income voices.

Single-member districts can trap neighborhoods with weak or unresponsive representatives for years.

At the end of the day, it all comes down to the person in the seat.

A good representative — one who understands they serve the whole community, not just one group — can succeed under any system. A bad representative will fail under any system.

The lines on the map matter less than the leadership that fills the chair.

A Local Way Forward

Honestly, the way Dalworth has handled it might be the best we can hope for. Instead of waiting on structural fixes, they built their own neighborhood civic group — a model David Daniels once suggested every part of Grand Prairie should follow.

That approach doesn’t change the voting maps, but it does strengthen representation where it matters most: neighbors speaking up together. And it does something elections alone can’t do — it keeps people engaged in the civic process more than once a year when they show up to vote.

If every district had that kind of organized voice, it would go a long way toward balancing the limits of our system and reminding city leaders that they serve the whole community, not just boundary lines.